What often draws us to this art is the idealized view of battles of old. Armour, mud and above all brave heroes fighting with swords. It’s a great image, a powerful image. One that has been passed down in culture from Morte d’Arthur through to Game of Thrones.

7 seasons and a movie are coming

Is it the correct image? That’s the question that would launch a thousand research papers and a million internet flamewars. I don’t intend to answer it partly because it’s highly contextual, partly because I’m too lazy to do the research, and partly because you can’t make me. What I am going to touch on is discussions of swords from military manuals from the 16th and 17th centuries.

The English language military manuals I’ll be discussing here mostly grew out of the translations of Roman manuals such as Epitoma rei militaris by Vegetius and Stratagems by Frontinus. Particularly towards the end of the 16th century these works begin to take a similar approach. Working out the flowchart of late 16th century plagiarism would be a paper in itself . Many begin to take on a similar form only differentiated by commentary or national variations. Jacob de Gheyn’s The exercise of armes for caliures, muskettes, and pikes is a much copied, and beautifully illustrated example of this style of work. Other influential translations include those of Count Jacopo Porcia and Luis Gutierres de la Vega.

Pike Illustration from Jacob de Ghent’s 1608 manual The exercise of armes for caliures, muskettes, and pikes

The main aim of these manuals was in the organisation, maneuvering, and logistics of running an army. Infantry in this age was divided into musketeers or harquebusers, pikes, halberdiers, and early on, archers. As you can see, swordsman is not an option. Occasionally there will be mention of targetters (which were generally attached to halberdiers or ensigns) but I found little mentioned of them beyond brief comments on specialized roles in flag defense or in breach work. Swords are distinctly seen as back-up weapons for when you run out of Option A.

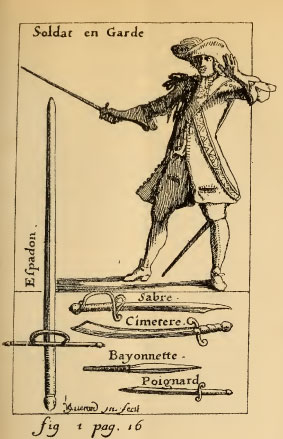

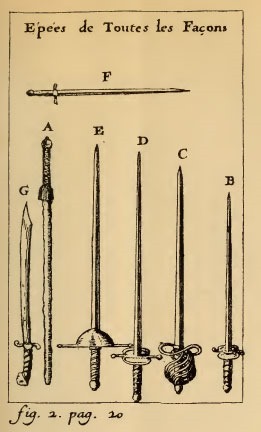

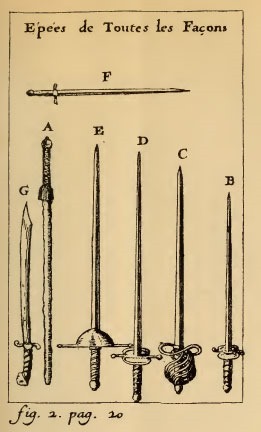

Illustration of swords from Gaya’s 1678 guide Traité des armes.

Of interest to us is the commentary about how soldiers should be armed. Often when it comes to side arms only the term ‘sword and dagger’ is used with no elaboration. However some manuals are specific about what type of swords their soldiers should have. In the 1594 imprint of the concisely titled [Certen] instruct[ions, obseruati]ons and orders militarie, requisit for all chieftaines, captaines [and?] higher and lower men of charge, [and officers] to vnderstand, [knowe and obserue] Sir John Smythe describes his ideal infantry sword.

The blades of their swordes I would haue to be verie good, and of the length of a yard and not aboue; with their hilts only made with 2 portes, a greater and a smaller on the out side of the hiltes, after the fashion of the Italian and Spanishe arming swordes

He discusses in his 1590 work, Certain discourses, vvritten by Sir Iohn Smythe, Knight: concerning the formes and effects of diuers sorts of weapons the reasons for having the length of the weapon less than a yard.

… whereas Swords of conuenient length, forme and substance, haue been in all ages esteemed by all warlike Nations, of al other sorts of weapons the last weapon of refuge both for horsemen, and footmen, by reason that when al their other weapons in fight haue failed them, either by breaking, losse, or otherwise, they then haue presentlie be taken themselues to their short arming Swords and Daggers, as to the last weapons, of great effect & execution for all Martiall actions: so our such men of warre (contrarie to the auncient order and vse Mililtarie) doo now a daies preferre and allowe that armed men Piquers, should rather weare Rapiers of a yard and a quarter long the blades, or more, than strong short arming Swords; little considering (or not understanding) that a squadrō of armed men in the field being readie to encounter with another squadron, their Enemies, ought to streighten and close themselues by frunt and flanckes, and that after they haue giuen their first thrush with their Piques, and being come to joyne with their enemies frunt to frunt, and face to face (and therefore the vse & execution of the piques of the formost rancks being past) they must presentlie betake themselues to the vse of their Swords and Daggers; which they cannot with any celeritie draw, if the blades of their Swords be so lōg: for (in troth) armed men in such actiōs, being in their rancks so close one to another by flanckes, cannot draw their Swords if the blades of them be aboue the lēgth of three quarters of a yard, or a little more: besies that, Swords being so long, doo worke in a manner no effect, neither with blowes nor thrusts where the is so great, as in such actions it is; as also, that Rapier blades being so narrow, and of so small substance, and made of a verie hard temper to fight in priuat fraies, in lighting with any blow vpon armour, do presently breake, and so become unprofitable.

The TL;DR is according to Smythe is:

- Long rapiers cannot be drawn from scabbards when troops are in close formation.

- Rapiers are too long to cause damage with cut or thrust (this might be due to difficulty maneuvering the weapon and a separate issue from below – but I’ll leave that interpretation to the internet)

- Rapier blades have no substance to them and are tempered in such a way they break against armour

In Certain Instructions Smythe expands upon his thoughts on the push of the pikes.

I thinke it may be apparant to all such as are not obstinatelie ignorant, that Battles and squadrons of piquers in the field when they doo incounter and charge one another, are not by any reason or experience mylitarie to stand al day thrusting, pushing, and foining one at another, as some doo most vainelie imagine, but ought according to all experience with one puissant charge and thrush to enter and disorder, wound, open, and break the one the other, as is before at large declared.

Earlier in the text he describes such a charge and the role of the sword and dagger in such an encounter.

But after all this it may be, that some very curious and not skilfull in actions of Armes, may demand what the formost rankes of this well ordered and practised squadron before mentioned shall doo after they haue giuen their aforesaid puissant blows & thrusts with their piques incase that they doo not at the first incountry ouerthrow and breake the contrary squadron of their enemies: ther vnto I say, that the foremost rankes of the squadron having with the points of their piques lighted vppon the bare faces of the formost ranks of their enemies, or vpon their Collers, pouldrons, quirasses, tasses, or disarmed parts of their thighes; by which blowes giuen they haue either slaine, ouerthrown, or wounded those that they haue lighted vpon, or that the points of their piques lighting vppon their armours haue glanced off, and beyond them; in such sort as by the nearnes of the formost ranks of their enemies before them, they haue not space enough againe to thrust; nor that by the nearnes of their fellowes ranks next behind them, they haue any conuenient elbowe roome to pull backe their piques to giue a new thrust; by meanes whereof they haue vtterly loste the vse of their piques, they therfore must either presentlie let them fall to the ground as vnprofitable; or else may with both their hands dart, and throw them as farre forward into & amongst the ranks of their enemies as they can, to the intent by the length of them to trouble their ranks, and presently in the twinkling of an eie or instant, must draw their short arming swordes and daggers, and giue a blow and thrust (tearmed a halfe reuerse, & thrust) all at, and in one time at their faces: And therewithall must presentlie in an instant, with their daggers in their left hands, thrust at the bottome of their enemies bellies vnder the lammes of their Cuyrasses, or at any other disarmed parts: In such sort as then al the ranks of the whol squadron one at the heeles of the other pressing in order forward, doo with short weapons, and with the force of their ranks closed, seeke to wound, open, or beare ouer the rankes of their enemies to their vtter ruine: At which time and action all the inner rankes of piques sauing the first, 4. or 5. ranks, can with their piques worke no effect, by reason that the said 4. or 5. rankes before them being next to their enemies, are so neare and close together, that they cannot with any thrust vse the pointes of their piques against their said enemies, without endangering or disordering their fellowes before them; For which causes by al reason and experience militarie, short staued, long edged, and short and strong pointed battleaxes or halbards, of the length of 5. foot or 5. foot and a halfe in all their lengths, at the vttermost, in the hands of lustie and well armed soldiors that doo follow the first 5. rankes of piquers at the heeles, doo both with blow at the head, and thrust at the face, worke wonderfull effects, and doo carrie all to the ground.

The TL;DR of this passage is:

- Once in range the first rank of pikemen get their points onto their opponent

- They thrust

- Either their opponent is dead, knocked down, wounded or their point has glanced off their armour

- Their use of the pike has been lost as they cannot pull back for another thrust and their point is past their enemies

- They either drop their pikes or throw them as far as possible into the enemy ranks.

- And here is the swordy bit – They draw their swords and daggers.*

- With the sword do a half reverse cut followed by a thrust to their opponents face. This appears to be a straightforward sequence.

- Draw the blade from the scabbard.

- Once clear deliver a reversa cut to the face. The description of the ideal sword hanger seems to match the images in de Ghent. This would make the reversa most likely a rising or horizontal cut.

- Follow up with a thrust to the face.

- After delivering the above close in with the dagger stabbing up under the opponents cuirass or other unarmoured area.

- Repeat until dead, till enemy runs/stops moving, or until the friendly maniacs with the halberds arrive to save you.

Drawing the sword from de Ghent’s 1608 manual.

Now of course this is the opinion of Sir John Smythe. There may be a large gap between what he thought should happen and what actually did. Pike warfare is not a specialty of mine, nor are military manuals of the 16th and 17th century for that matter. I’m sure more insights can be brought to this subject by wiser folks than myself. What the text does do is give a specific context to the use of the sword. It also lays out the the scope of battlefield sword use.

The next post will follow up on Smythe’s opinion on the best type of dagger to use, other detailed explanations of swords, and an opinion about if one should have fencers as soldiers.

* – Smythe advocated the sword worn “their hangers of such conuenient length, and so well formed as their swordes might hang vpon the vpper parts of their thighes; not only readie and verie easie to be drawen; but also by their well hanging of them straight forward and backward,” He thought the dagger should be worn on the right thigh.